Transvaginal Mesh Recalls & Discontinued Products

Transvaginal mesh products are sometimes used to repair pelvic organ prolapse (POP) or stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Despite thousands of reports of serious injuries leading to lawsuits being filed, only one transvaginal mesh device has been recalled. Though, several companies have discontinued their products.

Our content is developed and backed by respected legal, medical and scientific experts. More than 30 contributors, including product liability attorneys and board-certified physicians, have reviewed our website to ensure it’s medically sound and legally accurate.

legal help when you need it most.

Drugwatch has provided people injured by harmful drugs and devices with reliable answers and experienced legal help since 2009. Brought to you by The Wilson Firm LLP, we've pursued justice for more than 20,000 families and secured $324 million in settlements and verdicts against negligent manufacturers.

More than 30 contributors, including mass tort attorneys and board-certified doctors, have reviewed our website and added their unique perspectives to ensure you get the most updated and highest quality information.

Drugwatch.com is AACI-certified as a trusted medical content website and is produced by lawyers, a patient advocate and award-winning journalists whose affiliations include the American Bar Association and the American Medical Writers Association.

About Drugwatch.com

- 15+ Years of Advocacy

- $324 Million Recovered for Clients

- 20,000 Families Helped

- A+ BBB Rating

- 4.9 Stars from Google Reviews

Testimonials

I found Drugwatch to be very helpful with finding the right lawyers. We had the opportunity to share our story as well, so that more people can be aware of NEC. We are forever grateful for them.

- Medically reviewed by Dr. John A. Daller

- Last update: May 13, 2025

- Est. Read Time: 8 min read

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration cleared the first mesh product, the ProteGen Sling, for SUI in 1996. Boston Scientific recalled the product about three years later.

However, before the product left the market, the FDA cleared several additional products based on the ProteGen Sling’s design.

Over the last decade, the FDA has issued safety notices, convened advisory committees and even ordered manufacturers to stop selling surgical mesh for certain transvaginal repairs after reclassifying the medical devices as “high-risk.”

And more than 100,000 women have filed transvaginal mesh lawsuits against the manufacturers after experiencing complications, such as mesh erosion, organ perforation and infection.

Although other mesh manufacturers have discontinued their products, they’ve never issued recalls of their devices.

In 2019, FDA banned transvaginal mesh for treating pelvic organ prolapse. Then, in October 2022, FDA reaffirmed that transvaginal placement of surgical mesh to treat POP doesn’t outweigh the risks.

Boston Scientific Recalls ProteGen Mesh

The ProteGen Sling was the first transvaginal mesh product on the market and the first to be recalled. Boston Scientific recalled the device because of safety concerns in 1999. It remains the only recalled product of its kind.

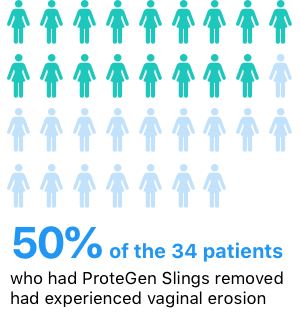

A small 1999 study published in The Journal of Urology found high rates of erosion, infection and pain with the device. To conduct the study, researchers with Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles reviewed records of patients who had their ProteGen Sling removed at five centers over the course of two years.

Half of the 34 patients who had their ProteGen Sling removed had suffered vaginal erosion only. Seventeen percent developed an urethrovaginal fistula, an abnormal connection between the urethra and the vagina.

“The FDA found that the product was associated with a ‘higher than expected rate of vaginal erosion and dehiscence’ and did ‘not appear to function as intended,’” Dr. L. Lewis Wall and Douglas Brown wrote in a 2010 article in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Prior to entering the market, the mesh sling did not undergo controlled clinical trials, and researchers had never implanted it in a human vagina.

“Boston Scientific relied on a 90-day study in rats and the fact that the mesh was already being used for cardiovascular grafting to gain approval from the FDA,” according to Wall and Brown. “The results were disastrous.”

But other manufacturers created their own transvaginal mesh products based on the ProteGen’s design.

Because of the similarities between the products and ProteGen, companies bypassed several clinical trial requirements by using the 510(k) clearance process. Section 510(k) of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act allows medical manufacturers to avoid human testing and deliver a product directly to the market if it is substantially equivalent to an already approved product.

The ProteGen recall didn’t affect the approval status of other devices.

FDA Safety Notices, Warnings and Surveillance Orders

The FDA was slow to act on evidence that transvaginal mesh products were causing dangerous complications in women. The agency first began receiving reports that mesh implants were causing unexpected side effects in 2005. It didn’t reclassify surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse as “high risk” until 2016.

During the decade before it reclassified the products, the FDA had issued a handful of safety notices and convened one committee meeting.

The agency finally ordered manufacturers to stop selling mesh for transvaginal repair of POP in the anterior compartment prolapse (cystocele) after an advisory committee meeting in 2019. By that time, all manufacturers had already stopped marketing mesh for transvaginal repair of posterior compartment prolapse (rectocele) as a result of the FDA’s actions.

However, SUI mesh and POP mesh implanted abdominally are still available.

Public Health Notification in 2008

On Oct. 20, 2008, the FDA notified the public of severe complications caused by transvaginal mesh. From 2005 to 2007, the agency had received more than 1,000 reports of adverse events associated with mesh, according to an article by Drs. Toyohiko Watanabe and Michael B. Chancellor in Reviews in Urology.

In 2010, roughly 75,000 women underwent transvaginal POP surgeries with mesh in the United States and more than 200,000 women received a transvaginal mesh implant to treat SUI, according to the FDA. From January 2008 through December 2010, the agency received an additional 2,874 adverse event reports associated with mesh used in POP or SUI repair.

The FDA advised physicians to monitor patients for adverse reactions, inform patients of the risks associated with the surgery and undergo training to learn to implant the devices.

Updated Safety Communication in 2011

In its 2011 Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh: Update on the Safety and Effectiveness of Transvaginal Placement for Pelvic Organ Prolapse, the FDA reiterated the recommendations it had made in 2008. But it updated its language to state that major complications are “not rare.”

The agency said it had not found conclusive evidence that using transvaginally placed mesh improves clinical outcomes any more than traditional non-mesh treatments, and it may expose patients to greater risks.

The FDA announced that it would form a committee to review and analyze the data concerning the safety and effectiveness of transvaginal mesh and provide recommendations to the agency.

September 2011 Advisory Committee Meeting

In September 2011, the FDA convened an advisory committee on the safety and effectiveness of transvaginal mesh devices. The panel received comments from medical professionals and patients.

Dr. Michael Carome, then deputy director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, urged the committee to recommend a recall of the device. According to Public Citizen, mesh poses significant risks to the public.

The group had petitioned the FDA to ban the device. It said that mesh implants were inadequately tested before being released to the public and that the FDA should require further testing of mesh products.

“Given the absence of evidence for clinically significant benefit and the overwhelming evidence of very serious, common risks, use of synthetic surgical mesh products for transvaginal repair of POP is not ethically justifiable,” Carome said in his testimony.

The panel refused to recommend a recall, but it recommended reclassifying transvaginal mesh as a class III device. The classification requires products to pass stringent tests before they can be marketed.

Postmarket Surveillance Orders

In January 2012, the FDA ordered transvaginal mesh makers to study the safety and effectiveness of their devices. The studies were part of an FDA program called the 522 Postmarket Surveillance Studies Program. Section 522 of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act gives the FDA the authority to order companies to study class II and class III devices. Transvaginal mesh devices were class II at the time.

By February 2013, the agency had ordered 34 manufacturers to study 95 mesh implants designed for use during pelvic organ prolapse surgery. The FDA also ordered seven companies to study 14 bladder slings indicated for treating stress urinary incontinence.

Reclassifying Transvaginal Mesh as Class III High-Risk Devices

In April 2014, the FDA submitted two proposals to reclassify transvaginal POP mesh. It finalized the proposed orders in 2016, and in January 2017, the FDA issued the final order.

The first order reclassified transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse surgery as a class III device. The second order required companies to submit a premarket approval application to support the use of mesh during POP surgery.

The orders did not apply to mesh used during stress urinary incontinence surgery. The companies were given until July 2018 to submit premarket approval applications.

Instead, all but one manufacturer of mesh for transvaginal repair of posterior compartment prolapse (rectocele) stopped selling their devices. In July 2018, the FDA ordered the last manufacturer to stop marketing the products.

February 2019 Advisory Committee Meeting and April 2019 Ban on Sales

On Feb. 12, 2019, the FDA held another advisory committee meeting to review the safety and effectiveness of mesh for transvaginal repair of prolapse.

In order to show the mesh was safe and effective, manufacturers had to prove it was superior to native tissue repair at 36 months and that the safety outcomes were comparable.

Boston Scientific and Coloplast were unable to provide adequate data to the FDA, and the agency ordered them to stop selling their products on April 16, 2019.

Companies that Discontinued Mesh Products

Several companies have voluntarily withdrawn products from the market without issuing recalls. When a company withdraws a medical device, it stops selling it. When it recalls a medical device, it warns the public of risks and usually pays for any complications and surgeries associated with the removal of the device.

Mentor Corporation Withdraws ObTape

Mentor Corporation’s ObTape Vaginal Sling was a piece of mesh used to treat incontinence in women.

To get clearance to sell its device, Mentor told the FDA the product was essentially the same as Johnson & Johnson’s Tension Free Vaginal Tape System, which had been cleared based on claims it was much like Boston Scientific’s recalled ProteGen Sling.

Surgeons implanted ObTape between 2003 and 2006 before its manufacturer withdrew it.

One of the biggest problems with the product was a high rate of vaginal extrusion, and some doctors had stopped using the product before it was discontinued. Experts claimed the product was too dense and did not allow capillaries and tissue to grow through it, causing the body to reject it.

Ethicon Pulls Mesh Products

In June 2012, Johnson & Johnson’s Ethicon unit stopped selling four of its Gynecare mesh products.

The following products were discontinued:

- Gynecare Prolift Kit

- Gynecare Prolift + M Kit

- Gynecare TVT Secur

- Gynecare Prosima Pelvic Floor Repair System Kit

The company stopped selling the products worldwide, but it didn’t recall mesh that had already been sold or implanted. The company stated that safety was not the reason it discontinued the devices. Ethicon continues to sell Gynecare Gynemesh, but the company changed the labeling to restrict its use to abdominal implantation.

Other Discontinued Devices

Rather than provide the FDA with new safety data, several companies discontinued their devices.

- Adjust TM Adjustable Single Incision Sling

- AMS Apogee and Perigee Systems

- AMS Single Incision Sling System

- Bard Avaulta Plus Biosynthetic Support System

- Bard Avaulta Solo Support System

- ECM Surgical Patch

- Ethicon Gynecare Gynemesh PS Prolene Soft Mesh

- Mentor Suspend Sling

- MiniSling

- Sofradim UGYTEX Dual Knit Mesh

- Sofradim UGYTEX Mesh

- Surelift Prolapse System

- Surgical Mesh, Polymeric (Promethean)

Manufacturers brought at least 61 mesh implants to market through the 510(k) clearance process by using Ethicon’s Mersilene Mesh and Boston Scientific’s ProteGen Sling, even if it was already recalled, according to authors Carl J. Heneghan and colleagues.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch.com representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch.com's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.