Women have made strides in almost all aspects of society, but discrimination is still alive in one of the last places anyone would expect: health care. When it comes to the availability of life-saving medical products and the safety of drugs and devices, men still have the upper hand. One of the greatest and most powerful health agencies in the world, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), is a big part of the problem.

Editors carefully fact-check all Drugwatch.com content for accuracy and quality.

Drugwatch.com has a stringent fact-checking process. It starts with our strict sourcing guidelines.

We only gather information from credible sources. This includes peer-reviewed medical journals, reputable media outlets, government reports, court records and interviews with qualified experts.

On September 24, 2015, Angela Desa-Lynch and a number of other women planned to hold a hunger strike on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) doorstep in Silver Spring, Maryland in the Washington, D.C. metro area. The group of women represented thousands of others injured by a birth control device called Essure that victims say needs to be pulled off the market. According to Desa-Lynch, the device that works by creating scar tissue in fallopian tubes is severely injuring and even killing women.

The hunger strike is set to begin the same day that the FDA holds a meeting to review the device’s safety. Since Essure was approved in 2002, the agency received more than 5,000 reports of adverse events, including the death of five unborn babies and four women. The FDA approved the device and granted the manufacturer, Bayer, preemption status – meaning those injured by the product cannot file a lawsuit against the company.

Thousands of women took to social media and formed support groups to get the FDA to take action. Desa-Lynch is just one of thousands affected by Essure who call themselves “E-sisters.”

“We’re just gonna stay there,” she told Vocativ.com about the hunger strike. “After five days is over, we’ll give them a couple months, and if they don’t pull Essure from the market, then we’re coming back and we’ll do it again.”

Should women really have to camp out in front of the FDA in order to be protected from bad medical devices?

The FDA’s questionable track record in protecting women’s health didn’t start with Essure, and women are still far off from being treated as equals when it comes to health. It wasn’t until 1994 that the FDA formed the Office of Women’s Health (OWH). The office’s mission is to “protect and advance the health of women through policy, science and outreach” – including “advocating for women in clinical trials and for sex, gender and subpopulation analyses.”

Real Women Pay the Price

The FDA’s history and actions don’t support the promise it made women over 20 years ago. Supposed FDA-approved products have led to serious injuries to women and their families, including life-altering, disfiguring surgical complications, birth defects in babies and onset of chronic disease.

One of those women is Vivianna Ruscitto, who never expected to have to worry about fighting for her life in a New York hospital bed, unable to care for her two-year-old son and leaving him without a mother after a routine surgery. After a hysterectomy with a surgical tool called a power morcellator, she was diagnosed with an aggressive stage 4 uterine cancer called leiomyosarcoma.

In August 2015, members of Congress called for an investigation of the FDA, the New York Times reported. “Hundreds, if not thousands of women in America are dead because of a medical device known as the laparoscopic power morcellator,” several lawmakers said in a letter to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

The FDA approved the first morcellator 24 years ago, and despite the fact that it knew the devices could shred cancerous tissue in the abdomen and spread it, it did not warn the public or require manufacturers to do so. It actually approved a total of 10 devices.

The problem didn’t start and end with power morcellators. The FDA has a long history of dropping the ball when it comes to women’s health – and beyond the numbers and statistics, it is real women who pay the price.

Clinical Trials and Research Underrepresent Women

One of the biggest hurdles to making drugs and devices safer for women is the lack of proper testing, specifically testing in early animal research and human clinical trials. One of the FDA’s tasks is to oversee clinical trials. A number of drugs and medical devices work differently in women than in men, yet many are never adequately tested in women.

According to 2022 data from the FDA’s Office of Women’s Health, females have nearly double the risk of developing an adverse drug reaction compared to men.

Yet, for decades, women were underrepresented in clinical trials, and the FDA didn’t start looking into the problem of gender equality in studies until the late 1990s. In fact, until 1988, clinical trials of new drugs were conducted on predominantly male subjects, though women consumed 80 percent of the pharmaceuticals in the U.S. at the time.

“How do we know that research that’s primarily done on young, White, healthy males can be extrapolated to women?”

FDA Bans Many Women from Clinical Trials, Sets Women’s Health Back

In the 70s, a drug used to prevent morning sickness called thalidomide was discovered to cause severe birth defects, such as missing limbs in children. In the wake of this disaster in 1977, the FDA even banned women who could become pregnant from participating in early-stage clinical trials. But, researchers ended up also excluding women who used contraception, were not sexually active or who were homosexual – a large subset of women. The ban set women’s health back a few decades and exposed women to dangerous side effects.

It took almost 20 years to reverse this mandate in 1993.

In 1993 the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act mandated the inclusion of women in clinical trials. However, this law only applied to NIH trials. Trials run by drug companies were under no obligation to comply with the Act, and 90 percent of all trials were (and are) funded by the industry.

With lack of enforcement, even the NIH had trouble following its own mandate.

Studies conducted by the NIH in the years following its much-lauded 1993 Act did include more women. Yet, about 75 percent of studies published in four major journals in 1993, 1995, 1997 and 1998 failed to analyze data by gender.

As it turns out, the FDA was actually excluded from this mandate, according to Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research, a non-profit advocacy group in D.C.

“How does it make any sense that the agency that’s deciding which drugs and devices should be approved is the one that doesn’t have to worry if there are women or people of color or people over 65 or any other group in the clinical trials?” Zuckerman told Drugwatch.

By 2001, two thirds of trials still excluded women. While 91 percent of studies found evidence that gender made a difference in the way drugs were metabolized or in the occurrence of adverse reactions, scientists failed to analyze results.

Gender Bias in Animal Research Puts Women at Risk

The problem of gender bias in medical research still exists. Not only is there a problem with human participation and data analysis, but even animal studies are affected. Researchers prefer male animals because male physiology is easier to study. They are not required to use female animals in studies, which means scientists overlook key differences in how drugs affect men and women.

“Medical research that is either sex- or gender-neutral or skewed to male physiology puts women at risk for missed opportunities for prevention, incorrect diagnoses, misinformed treatments, sickness and even death,” said researchers from Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health & Gender Biology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The FDA hasn’t made a move to enforce any specific practices.

However, in 2014, U.S. Rep. Jim Cooper of Tennessee and U.S. Rep. Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming introduced a bipartisan bill called the Research for All Act that would mandate that the FDA guarantee clinical drug trials for fast-tracked drugs take safety into account for both men and women.

“One sex should not be excluded from testing when it could mean the difference between effective treatment and harm to health.”

“The Research for All Act requires thorough research to ensure viable and effective medicines for both men and women,” Lummis said on the bill’s website. “One sex should not be excluded from testing when it could mean the difference between effective treatment and harm to health.”

Even when women participate in trials, researchers still fail to study the data by sex, hormone or gender-specific factors. Lack of testing didn’t stop the FDA from allowing drug companies to continue selling potentially dangerous drugs to women, either.

In October 2014 the NIH mandated that all grant applications must detail how researchers plan to equalize sexes in their studies using lab mice. This is a step in the right direction. However, the majority of clinical trials are conducted by private companies without NIH grants.

Unsafe Drugs Pulled from Market Pose Greater Risk to Women

Some experts connect the lack of women in clinical trials to the number of side effects women suffer from drugs. The FDA rarely requires drugs to be pulled from the market. In 2000, the GAO examined several drugs that the FDA approved for widespread use and then later pulled for safety issues – 8 out of 10 of these drugs posed more of a threat for women.

These drugs caused a variety of severe problems including: valvular heart disease, potentially fatal irregular heartbeat called Torsade de Pointes, liver failure, ischemic colitis (intestinal inflammation because of lack of blood flow) and lowered heart rate. One of the drugs, Pondimin (fenfluramine hydrochloride) – a drug highly prescribed to women, was on the market for over 20 years before it was finally pulled.

| Name | Type | Date Approved | Date Withdrawn | Health Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pondimin (fenfluramine hydrochloride) | Appetite suppressant | 6/14/1973 | 9/15/1997 | Valvular heart disease |

| Redux (dexfenfluramine hydrochloride) | Appetite suppressant | 4/29/1996 | 9/15/1997 | Valvular heart disease |

| Seldanea (terfenadine) | Antihistamine | 5/8/1985 | 2/27/1998 | Torsades de Pointes (potentially fatal irregular heartbeat) |

| Posicor (mibefradil dihydrochloride) | Cardiovascular | 6/20/1997 | 6/8/1998 | Lowered heart rate in elderly women and adverse interactions with 26 other drugs |

| Hismanal (astemizole) | Antihistamine | 12/19/1988 | 6/18/1999 | Torsades de Pointes |

| Rezulin (troglitazone) | Diabetic | 1/29/1997 | 3/21/2000 | Liver failure |

| Propulsidb (cisapride monohydrate) | Gastrointestinal | 7/29/1993 | 7/14/2000 | Torsades de Pointes |

| Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) | Gastrointestinal | 2/9/2000 | 11/28/2000 | Ischemic colitis (intestinal inflammation due to lack of blood flow) |

FDA Ignores Data about Women's Drug Risk

Ideally, clinical trials should provide insight on how certain drugs may affect a woman differently than a man, and this information should be available to women. Yet, there is little action from the FDA or drug makers even when information is available.

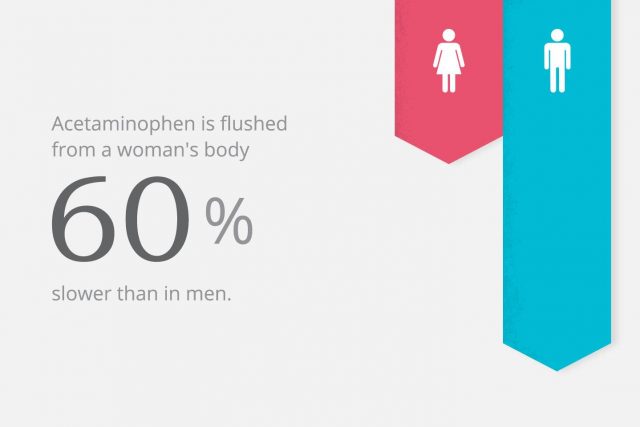

For example, studies now show that acetaminophen – the active ingredient in popular over-the-counter pain reliever Tylenol and a number of other medications – is flushed from a woman’s body 60 percent slower than in men. The FDA and Johnson & Johnson – Tylenol’s makers – never included an adjusted dose for women or warned about this fact, putting women at risk for a potential overdose that could cause acute liver failure.

A more recent example of how the lack of gender-based drug information can harm women came out in early 2014. The CBS show “60 Minutes” did a report on the sleeping pill Ambien. Each year doctors write about 40 million prescriptions for the drug. It was originally approved in 1992, and more than 20 years later, studies surfaced revealing that women were taking more of Ambien than they needed because of incorrect dosage instructions, and as a result, increasing the risk for impaired driving.

The FDA cut the dose in half for women in 2014, but it turns out the agency knew about the problem in 1992 when it received clinical data showing the amount of Ambien in a woman’s blood was 45 percent more than in a man’s.

The FDA failed to act.

“If I saw this today, in light of today’s science, I think we would go back and try to tease this out a little bit further. But I think at the time…this was sort of business as usual for what you saw in clinical pharmacology studies,” Dr. Sandra Kweder, deputy director of the FDA’s Office of New Drugs, told Lesley Stahl of “60 Minutes.” Ambien is the first and only drug that provides a specific dose for women.

For more than two decades, millions of women were overdosing on Ambien. How many other facts is the FDA ignoring?

If the FDA had properly labeled and assessed Ambien’s effect on women, Julie Ann Bronson might not have ended up in jail, confused and scared. In 2009, Bronson took Ambien to help her sleep. The next morning, she was in her pajamas, barefoot and terrified in jail. She was told she ended up going for a drive and hitting two people, one of which was an 18-month-old-girl who suffered severe brain damage. She had no memory of the incident.

Bronson ended up pleading guilty to two felonies, intoxication assault and failure to stop and render aid, in May of 2012. “I did the crime but I never intended to do it,” she testified. “I wouldn’t hurt a flea. And if I would have hit somebody, I would have stopped and helped.”

She was sentenced to 10 years, but because her lawyers argued that Ambien played a part in the offense, the sentence was reduced to six months in prison and ten years of probation.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES)

DES was first approved in 1941, but doctors used it off-label to prevent miscarriages in the 1940s. The FDA approved it for this use in 1947.

Published studies soon came out in 1953 that showed the drug did not prevent miscarriage, but the FDA took no action to stop doctors from prescribing it for this use in pregnant women. Nearly 20 years later, millions of women had taken the drug.

In 1971 research showed DES ended up causing vaginal cancer or infertility in daughters of women and doubled the risk of breast cancer in women who took it. Finally, the FDA released a warning that all pregnant women should stop taking DES.

Prempro

Pfizer’s hormone replacement drug, Prempro, made headlines after the company paid close to one billion dollars in 2012 to settle lawsuits filed by women who were diagnosed with breast cancer after taking the drug and other similar ones. The drug is an estrogen and progestin combination hormone replacement therapy (HRT) intended to treat symptoms of menopause in women.

Despite a number of studies published as far back as 1979 detailing that the risks of HRT outweighed the benefits, the FDA approved the drug in 1995. In 2000, the FDA’s Dr. Susan Allen, director of Reproductive and Urologic Drug Products requested Wyeth make this change to the drug’s label:

“The addition of progestin to estrogen may increase the risk for breast cancer over that noted in non–hormone users more significantly (by about 24–40percent), although this is based solely on epidemiologic studies, and definitive conclusions await prospective, controlled clinical trials.”

Despite knowing the significant increased risk of breast cancer the FDA did not require a black box warning or ban the drug. In 2002, the Women’s Health Initiative stopped a trial involving HRT because the risk outweighed the benefits.

Unborn Children at Risk

“The essence of social justice is to treat others as dignified beings deserving of equal moral concern and to view others as independent sources of moral worth and dignity. By that standard, the current state of clinical research is disrespectful of pregnant women.” – M. A. Foulkes et al., Clinical Research Enrolling Pregnant Women: A Workshop Summary

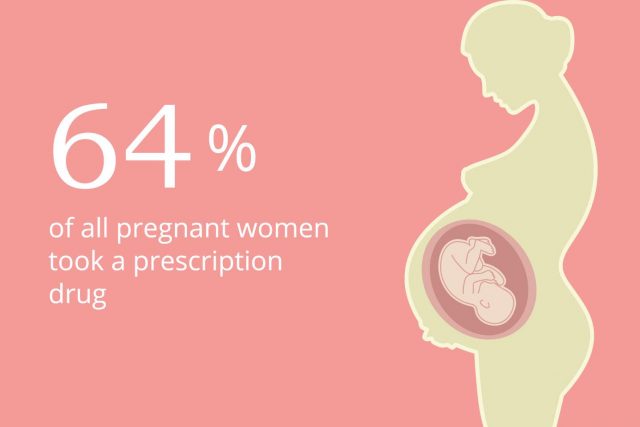

Unfortunately, it isn’t just women that are affected. Many of the drugs expectant mothers take have consequences for their unborn children, from rare cancers to serious birth defects. Part of the problem is the lack of clinical data involving expectant mothers.

Because of concerns with protecting the fetus, pregnant women are routinely excluded from clinical trials. However, excluding pregnant women only leads to drugs and devices being “tested” on them in an uncontrolled environment once these products hit the market.

The majority of pregnant women typically take drugs during pregnancy. According to one study, 64 percent of all pregnant women took a prescription drug. When mothers do make the decision to take medication, they may be leaving their baby’s safety to chance.

Pregnant Women and Antidepressants

In particular, antidepressant use in pregnant women is on the rise. One in eight pregnant women uses an antidepressant. The risk of any drug taken during pregnancy must outweigh the risk. However, with a lack of good data to make a decision, many women are often forced simply to make a decision that could be harmful to them or the baby.

Some studies show that between 20 to 30 percent of newborns exposed to SSRIs suffered disorders from seizures to agitation and abnormal muscle tone. Other studies showed all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of antidepressants, increased risk of heart or brain malformations by double.

The popular antidepressant Paxil was approved in 1992. Several years later in 2005, the FDA issued a warning for birth defects, but only required the drug’s maker to change the pregnancy rating of the drug from C to D – meaning the drug posed a risk to the baby. Other drugs in the same class may also cause birth defects, but the FDA has yet to advise mothers of these risks.

SSRIs are now involved in a number of lawsuits filed by mothers whose babies suffered birth defects. In June 2015, a report from Pfizer surfaced showing the company knew about the possible birth defect risk of its blockbuster multi-billion-dollar antidepressant, Zoloft, since 1998.

Was the FDA aware of these risks as well? Did the agency simply ignore the findings as it did in the case of Ambien? While it now warns pregnant women about Paxil, it does not do enough to warn about the risks of all SSRIs.

Untested Medical Devices Ruin Women’s Lives

While the FDA’s drug oversight leaves much to be desired, some of the most horrific adverse events to affect women stem from medical devices. The shocking truth is that the FDA allows medical device companies to sell their products without proving that they are safe and effective through a program called the 510(k) clearance process.

For a fee of about $4,000, manufacturers get to sell a device as long as it is “substantially equivalent” to one already on the market. The result is that women – and men – are forced to be guinea pigs for poorly tested devices.

In the case of women who are involved in less medical testing than men to begin with, this does not bode well. Three of the most controversial medical devices hurting women are transvaginal mesh, power morcellators and Essure birth control.

Transvaginal Mesh

After Estelle Tasz was implanted with mesh to treat a prolapsed bladder, her life was never the same. “I would hemorrhage just walking into a store,” Tasz told Drugwatch. “They would have to transfer me by ambulance, because as you know, you are bleeding out. That happened about three times in one year.”

After surgery to remove the mesh, doctors discovered the implant – which in appearance resembles a piece of window screen – had migrated through her vaginal wall and fused into her abdominal wall.

Close to 100,000 women implanted with transvaginal mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse – a condition where organs sag into the vagina – or stress urinary incontinence are clamoring for their day in court after they claim mesh products eroded vaginal and pelvic tissues, causing considerable pain, depression and nerve problems. The group of cases is one of the largest is U.S. history.

“[Mesh is] a 'poster-child' example of the fundamental failure of the 510(k) premarket notification process to protect the public’s health and welfare.”

“I dare to be as bold to say this is almost like genocide on women,” Teresa Sawyer, who had mesh implanted, told Drugwatch. Her husband David, added, “It baffles me that this is happening in America – or anywhere.”

While lawsuits blame manufacturers for failure to warn and for manufacturing faulty products, experts blame the FDA’s lack of action.

“I dare to be as bold to say this is almost like genocide on women.”

The FDA approved the first mesh device, Boston Scientific’s Protogen, in 1996. In 1999, the device was recalled for safety reasons, yet a significant number of products on the market were all cleared for sale based on this recalled device.

Consumer watchdog group Public Citizen petitioned the FDA to ban the product and require all manufacturers to issue recalls in 2011. According to extensive studies presented by the group, mesh offers no significant clinical benefit in comparison to surgical repairs without mesh.

Finally, in 2011 the FDA released an executive summary called Surgical Mesh for Treatment of Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence. In 2014, the agency announced it was considering reclassifying the devices from Class II to Class III, which would require companies to provide data that mesh products are safe prior to selling them.

“The FDA has identified clear risks associated with surgical mesh for the transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse and is now proposing to address those risks for more safe and effective products,” said Dr. William Maisel, deputy director of science and chief scientist at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in response to the reclassification consideration.

Yet, despite its own data showing mesh to be risky, it approved Caldera Medical’s new mesh product, Vertessa Lite, in 2015. Caldera is one of the companies embroiled in mesh litigation. Naturally, this product was approved before the FDA acted to reclassify all mesh devices, so it skated through without additional testing.

Power Morcellators

Imagine being told you are going in for a routine, minimally invasive procedure that will take less recovery time and improve your health only to discover later that the procedure can produce a dangerous side effect – spreading undetected uterine cancer in the body of the patient.

That is what happened to a number of women who went in for routine fibroid removal or hysterectomies with power morcellators, drill-like devices that shred up tissue and suck it out of the body cavity though a small incision.

The problem is shredded tissue can harbor undiagnosed uterine cancer. When bits of tissue are sprayed around the abdominal cavity, the cancer spreads.

The first FDA-approved laparoscopic morcellator appeared in 1995 through the 510(k) process. And since then, a couple dozen more have made it onto the market.

In 2009, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) issued a statement naming vaginal hysterectomy the best operation for removing benign disease. In 2012, a study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston pointed to a 9-fold higher risk of leiomyosarcoma than previously thought.

Further, they said the risk of spreading cancer in the uterine cavity was much higher than previously suspected.

In 2013, the Wall Street Journal published the story of Dr. Amy Reed, a woman who underwent morcellation and was later diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma. She and her husband, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, launched a campaign against morcellation. The FDA announced the risk of unsuspected uterine sarcoma is 1 in 352, and the risk of morcellating an unsuspected uterine leiomyosarcoma is 1 in 498.

The agency said it was only aware of the danger recently, but evidence of the risk has been around since the 1990s.

“The urban legend was 1 in 10,000 women who have a uterine fibroid removed [could have cancer]. But you know, as far back as the early 1990s they knew [the risk was worse]. One study indicated 1 in 40 of these fibroids were leiomyosarcoma,” Mike Pedersen, an attorney with New York-based law firm Weitz & Luxenberg, told Drugwatch.

Congress called for the GAO to investigate the FDA and why it took so long (over 20 years) to warn women of the danger. In September 2015, the government watchdog confirmed that it would initiate an investigation, the Wall Street Journal reported. The FDA said it would cooperate but had no comment.

Essure Birth Control

Essure is a flexible metal coil inserted by a doctor into the fallopian tubes. Over about three months, tissue forms around the coils and prevents sperm from reaching the egg. The device is a permanent form of birth control that is supposed to remain in the woman’s body forever.

The FDA approved the device manufactured by Bayer in 2002, and since then, thousands of women filed reports with the agency over terrible side effects such as back pain, cysts and even the need for hysterectomies to treat related issues. With lack of federal action, women turned to the courts to seek justice against Bayer. But, an FDA preemption rule prevents victims from filing lawsuits.

According to attorney Robert Jenner with Janet, Jenner and Suggs, the rule protects device makers from being sued because the FDA scrutinizes their devices more thoroughly.

“This is a $100-billion industry. There’s simply not enough money, not enough time and not enough people in the FDA to give it the oversight, the attention that it needs,” Jenner told WMAR News in Baltimore.

In essence, the FDA let a dangerous device through and barred anyone affected from seeking recourse and gave the device maker a free pass.

“This has really blown up and every day we have a handful of women that come and they tell us their stories and tell us their symptoms,” Krystal Donahue told WMAR. “It’s hurting us, and I really feel like the FDA has let us down.”

Women who say they were injured by Essure sent the agency a petition to recall the device in March 2015, according to reports by ABC 15 News in Arizona. Attorneys Marcus J. Susen and Justin Parafinczuk, who represented several clients, filed the petition on the women’s behalf. According to the petition, Conceptus, the original manufacturer of the device, perpetrated fraud during clinical trials and violated the terms of the FDA’s premarket approval.

The agency said it was investigating the claim. The agency also released an announcement that it plans to convene a public meeting of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel on September 24, 2015 to discuss recommendations.

Consumer advocate Erin Brockovich took up the fight alongside the women by campaigning on her website. “It is a woman’s right to decide for herself if she wants a certain form of birth control but when they are NOT told of the devastating side effects, well that isn’t right,” Brockovich said on her site.

In the meantime, women are still being affected by the device.

Twice Rejected 'Female Viagra' Gets Pushed Through

When the FDA actually rejects a drug because studies do not prove it is effective or safe, it backs down in the face of political and industry pressure. In June 2015, it recommended the approval of Addyi (flibanserin), the “little pink pill” being touted as “Women’s Viagra.” The drug was turned down twice for lack of evidence.

In August 2015, the approval became official, and uproar from the media and critics called the move an FDA “blunder.”

Despite the fact that Sprout Pharmaceuticals could not provide additional proof of safety and efficacy, the agency bent under pressure from a group called Even the Score, claiming the FDA was sexist. Cindy Pearson, executive director of National Women’s Health Network, wrote in the Washington Post, “I’m a pro-sex feminist, but I believe that advocating for women’s health means finding solutions for women’s sexual problems that are safe and effective. That hasn’t happened. Not yet.”

Pearson goes on to explain that Even the Score – a campaign backed by Sprout – brought people to speak on behalf of flibanserin and appealed to the emotions of FDA panelists, and that the campaign “fueled the charge that sexism is behind the FDA’s decision on women’s libido drugs.”

The facts about flibanserin are hardly optimistic for women hoping for relief from sexual dysfunction. The drug was only about 10 percent effective in trials and rife with serious side effects like low blood pressure and loss of consciousness. The average gain in “satisfactory sexual experiences” was only one more per month compared to placebo.

Plus, the drug interacts poorly with a number of medications, including fluconazole, a drug commonly used to treat female yeast infections. It also causes low blood pressure and fainting when combined with alcohol. The trial was stopped because of the danger the drug posed to participants – who were mostly male.

Dr. Sidney Wolfe, founder of the non-profit watchdog group, Public Citizen, calls it “FDA’s big mistake.” “Expect future news to include stories of women who are harmed needlessly by flibanserin and the eventual agency call for the manufacturer to pull it from pharmacy shelves,” Wolfe said in a statement.

How to Make an FDA that is Proactive, not Reactive

The majority of Americans mistrust the FDA, and each year faith in the agency that is supposed to protect us continues to flounder. In 2008, only 35 percent of Americans had a positive opinion of the agency – according to a Harris interactive survey by the Wall Street Journal. That figure improved only slightly to 45 percent in a Gallup poll in 2013.

What we need is an FDA that is proactive in safeguarding women’s health, not reactive and only taking action after the media steps in or lawsuits are filed.

One strong example was the thalidomide tragedy in the 60’s. A woman named Frances Oldham Kelsey began working at the FDA as a medical officer in charge of reviewing drugs for approval and licensing. An application for a medication named thalidomide – a sedative used to combat morning sickness in pregnant women – came across her desk.

“No one should leave women's health up to chance.”

Despite public pressure she denied the drug licensing because of a lack of evidence of safety. She received a lot of criticism for not approving the drug. Not long after, about 10,000 women and their unborn children all over the world found out the hard way that the drug caused serious birth defects, and children were born with missing limbs. The impact in the U.S. was minimal thanks to Kelsey’s diligence, and President John F. Kennedy presented her with the President’s Medal for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service.

We need more people like Kelsey and an FDA willing to put people before politics.

Government and research leaders need to step up and bring equality into clinical research.

This means the following agencies should lead the way and put pressure on private companies to do the same:

- National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

There are ways for people to get involved and make a difference.

Here are a few organizations that have been fighting and advocating for women’s rights in health:

- National Women’s Health Network

- The Society for Women’s Health Research (SWHR)

- National Center for Health Research

Demand that policy makers create laws that women in all stages of life be included in all phases of medical research and that data must be reviewed with both sexes in mind. No one should leave women’s health up to chance.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch.com representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch.com's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.