Boston Scientific

Boston Scientific is a Massachusetts-based company that manufactures products for various medical uses. By 2017, the company had developed more than 13,000 medical products marketed in 100 countries around the world.

Boston Scientific is a Massachusetts-based medical device company with a focus on noninvasive treatment – primarily of cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, digestive, urological and pelvic conditions. Its first major product was an angioplasty balloon for cardiovascular treatments, introduced in the late-1970s. By 2017, the company had developed more than 13,000 medical products marketed in 100 countries around the world.

Its business structure is built around these sectors: cardiovascular, rhythm management (cardiac management and electrophysiology), and MedSurg, or medical and surgical (endoscopy, urology, pelvic health, and neuromodulation – a form of central nervous system treatment).

In 2021, the company reported $11.88 billion in total revenue.

Boston Scientific experienced significant financial and litigation issues in the mid-2000s that continued to affect its bottom line for most of a decade. By the mid-2010s, the company was believed to have turned a corner through restructuring of the organization and addressing legal claims from individuals and the federal government through a series of high profile settlements.

By 2015, Boston Scientific claimed that a doctor used one of its devices every 16 seconds to treat peripheral artery disease and a patient was treated every 21 seconds with one of its urology products.

But Boston Scientific has recalled some of its products, sometimes in what the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has categorized as Class I recalls. These are “situations in which there is a reasonable probability that the use of or exposure to a violative product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death.”

Boston Scientific’s History: Innovation and Acquisitions

John Abele and Pete Nicholas founded Boston Scientific in 1979 with a vision of advancing low-cost, less invasive surgical and treatment procedures.

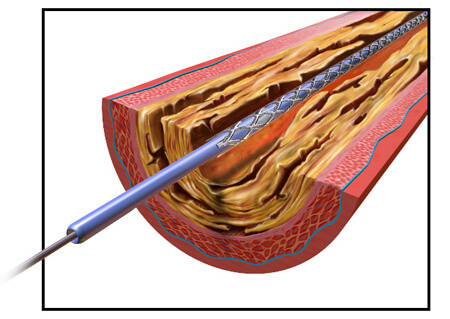

Their early focus made the company a pioneer of medical devices used in angioplasty – the surgical repair of blocked or narrowed blood vessels, particularly coronary arteries. One of the company’s first devices was a peripheral angioplasty balloon that could be inserted in blood vessels and inflated to expand the vessel and alleviate blockage. The device cemented Boston Scientific as a manufacturer of cardiovascular devices and helped underwrite the company’s growth.

In 1981, Boston Scientific acquired Endo-Tech, the company’s biggest competitor in producing accessories for endoscopes. In 1988, it acquired stent-maker Van-Tech. The acquisitions allowed the company to expand its reach across medical device markets affecting cardiology, pulmonary, urology and gastroenterology fields.

The company went public in 1992 and saw continued growth through the decade. By 1997, Boston Scientific had acquired nine additional companies and reported $1.8 billion in revenue for the year.

In 2004, the company acquired Advanced Bionics, which built neuromodulation devices – devices that treat disease by enhancing or suppressing activity in the central nervous system.

In 2003, the company’s Taxus Express2 stent was approved in Europe. When it received FDA approval in 2004, the company already had roughly 200,000 units ready to ship in the U.S. In 2005, the Boston Globe called the stent Boston Scientific’s “most important product ever” from a business standpoint.

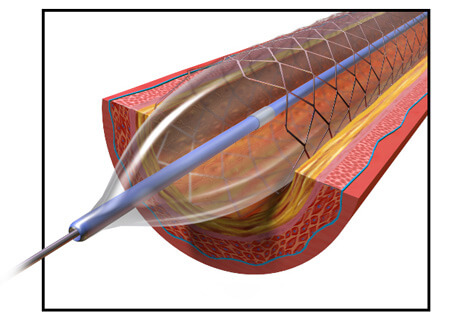

The Taxus Express2 is a stainless steel stent with a polymer coating. Stents work to expand a narrowed artery or vein, but sometimes the vessels will narrow again even after a stent is implanted. The Taxus system includes a medication built into its design to prevent the blood vessels from renarrowing. The drug – paclitaxel – is added to a polymer coating on the stent and is slowly released over about two weeks after the stent is implanted.

Boston Scientific closed three plants and laid-off thousands of workers to come up with part of the $350 million it needed to develop the device. The Taxus system was only the second device of its kind on the market, and an important new product for Boston Scientific. But its roll out was marred by a partial recall of 85,000 of the devices.

To install the stent, a catheter is threaded through blood vessels to the point that needs expanding. Then the stent is pushed through a catheter, into place in the narrowed vessel. A balloon inside the stent expands, enlarging the diameter of the stent to widen the vein or artery. Normally, the balloon deflates and is withdrawn back out the catheter, leaving the stent in place. But some of the balloons failed to deflate, leading to the recall.

Despite the recall, the device was a huge success for the company and helped drive up Boston Scientific’s profits more than five-fold in 2004.

Boston Scientific’s Growth Slows to a Crawl with Guidant Purchase

The Taxus Express2 was a gamble that paid off in a big way for Boston Scientific. But another gamble would leave the company reeling for nearly a decade.

In 2006, Boston Scientific acquired Guidant for $27.2 billion, the largest acquisition to date. Guidant produced cardiovascular devices including implantable defibrillators and pacemakers.

In 2016, the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported that the Guidant purchase was a long-term, and costly, problem for Boston Scientific. Business analysts said the company overpaid for Guidant, partly because of a bidding war with Johnson & Johnson driving up the price, and partly because there was no growth in its market sector. In addition, executives at Guidant hid problems with the company’s defibrillators before the sale.

Faulty capacitors in some of the devices caused their batteries to drain prematurely. This could result in patient death if the devices were unable to work properly.

After the acquisition, Boston Scientific was left to deal with the results and expenses when the problems came to light. In 2011, Guidant LLC pleaded guilty to federal misdemeanor charges of concealing the capacitor problems from the FDA, and Boston Scientific paid $254 million in criminal fines to the federal government.

In 2015, Boston Scientific settled a $7 billion lawsuit Johnson & Johnson filed against it over a dispute about how the Guidant acquisition turned out. Johnson & Johnson had claimed it had made a deal with Guidant to purchase the company, but Guidant broke its contract when Boston Scientific made a better offer.

The case had already cost Boston Scientific millions in legal fees and the prospect of losing in court had hung over the company’s financial planning for years. Boston Scientific paid $600 million to its former bidding war rival to settle the lawsuit.

Boston Scientific was also saddled with Internal Revenue Service penalties and interest over the Guidant purchase. In 2016, the company settled a $1.3 billion tax dispute with the IRS for $275 million plus interest, all to be paid by mid-2018.

The Guidant acquisition marked a turning point in Boston Scientific’s history.

Even as it was dealing with the mounting expenses from Guidant, Boston Scientific was being hit with thousands of product liability lawsuits over Boston Scientific’s transvaginal mesh (TVM). Boston Scientific reported a net profit in only two of the next ten years and went through multiple CEOs, lay-offs and restructurings before appearing to turn a corner in the 2010s.

Resuscitating Cardio Giant Boston Scientific

The business built on cardiovascular devices in the 1970s needed business CPR by the 2000s. Following the Guidant purchase and the baggage that came with it, Boston Scientific saw its market value plummet 78 percent. Product development and acquisitions had been disrupted and management was shaken by rapid turnovers. The company went through three CEOs in five years before Mike Mahoney, formerly with rival Johnson & Johnson, took the helm in 2012.

As president, chairman and CEO, Mahoney restructured Boston Scientific management in an effort to stabilize the company. At the same time, he saw Boston Scientific bogged down by expensive legal, management and regulatory distractions and sought to return the company’s focus to developing new devices and acquiring new companies – the hallmarks of its former success. He also acted quickly to reduce potential litigation costs, seeking settlements in a 15-year running legal battle with the IRS and Johnson & Johnson’s $7 billion lawsuit over the Guidant purchase and with nearly 40,000 patients suing over TVM.

As the company recovered financially, Boston Scientific began expansion into Chinese and Indian markets and acquired more companies with a focus on urology and cardiovascular products. Boston Scientific’s recent acquisitions have been restrained, going for smaller companies that can easily fit into its existing market sectors instead of attempting large takeovers and market expansions like the Guidant purchase.

By 2016, Boston Scientific was not only returning to profitability but was seen by some business analysts as a potential takeover prize itself.

Revolutionary Medical Devices, a Boston Scientific Signature

Boston Scientific has a record of developing revolutionary medical devices. In recent years, these have included modifications of its traditional products and designing devices that take the place of the drugs used in current medical treatments.

Advances on the Taxus drug-eluting stent include the Promus Element Plus, a platinum and chromium stent with a new generation drug element to prevent renarrowing of blood vessels. The company’s Eluvia drug-eluting vascular stent, not yet available in the U.S., was undergoing clinical trials into 2017. Boston Scientific claims the trials have “unprecedented results” after two years of study.

The company’s Alair bronchial thermoplasty system is billed as “the first and only” non-drug treatment for adults with severe asthma. A thin tube is threaded into the patient’s mouth or nose, along airways into the lungs. An electrode extends, heating targeted parts of the airways, reducing smooth muscle and limiting the passages’ contractions during an asthma attack.

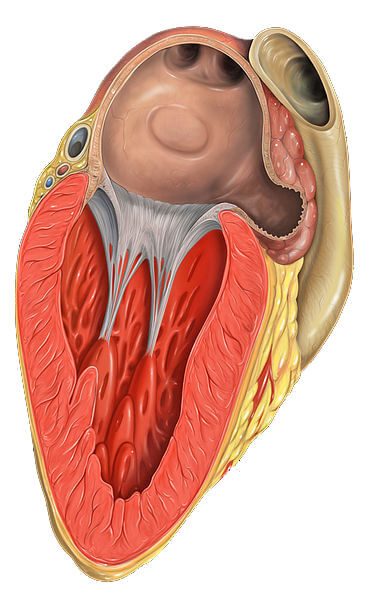

The Watchman Left Atrial Appendage (LAA) closure device is meant to be an alternative to blood thinners for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF). Arterial fibrillation (AF) is the most common kind of irregular heartbeat. NVAF is a sub-category of AF in which the heart rhythm disturbance happens without certain heart valve diseases, a prosthetic heart valve or surgical heart repairs.

Treating these patients with the anticoagulant warfarin can reduce their chance of stroke by 68 percent. But blood thinners come with complications, including the risk of uncontrolled bleeding.

The Watchman is a small, cage-like device that is placed in the LAA – a portion of the heart’s top left chamber called the left atrium. The device is inserted through a noninvasive catheter procedure. It closes off the appendage where blood clots are likely to form, possibly reducing the risk of stroke and allowing the patient to stop taking anticoagulants.

Lawsuits and Recalls Hurt Boston Scientific’s Bottom Line

Revolutionary medical devices sometimes come with high risks. Some other Boston Scientific devices on the cutting edge of technology have also been the subject of recalls and thousands of product liability lawsuits in recent years, resulting in billions in lost revenue.

Transvaginal Meshes

In 1999, Boston Scientific received FDA approval for the first transvaginal mesh (TVM) marketed in the U.S. The company would recall its ProteGen TVM just three years later, after a study found half of all women implanted with it developed serious health problems.

From 2014 through 2016, Boston Scientific annual reports showed more than $2.9 billion in litigation-related charges, largely related to transvaginal mesh (TVM) cases and claims.

In 2014 and 2015, juries returned four verdicts totaling more than $218 million in favor of plaintiffs who sued over Boston Scientific’s TVM. In a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in April 2015, the company announced it would pay roughly $119 million to resolve 2,970 cases.

By November 2016, the company said it had settled roughly 19,000 of the roughly 40,000 lawsuits over three versions of its TVM and five versions of transvaginal slings. Boston Scientific’s 2016 annual report said that the company had spent $806 million in litigation charges for the year, which included “primarily amounts related to transvaginal surgical mesh product liability cases and claims.”

Implantable Defibrillators

In 2007, the year after acquiring Guidant, Boston Scientific recalled 73,000 implantable heart devices manufactured by its new acquisition. The implantable defibrillators and defibrillator/pacemaker combination devices had faulty capacitors. This could cause batteries to drain sooner than expected, putting patients’ lives at danger.

Heart Valve Systems

In 2014 and 2016, Boston Scientific recalled several units of its first-generation Lotus heart valve systems for various problems. The 2016 recall followed three patient deaths in Europe.

In 2017, the company again recalled its Lotus devices, this time due to a manufacturing defect that made some of the devices difficult to implant. The recall did not affect those devices already implanted. The cumulative recalls raised investor concerns about Boston Scientific’s ability to crack the market for the product, dominated by two competitors – Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic Plc.

The recall included the new Lotus Edge devices in Europe, and caused the company to delay its marketing application for U.S. approval for the Edge versions.

The recall was a financial setback for the company, expected to keep the devices off the market for at least half a year in Europe and delay marketing the devices in the U.S. for a year. The Lotus devices had been expected to bring in up to $125 million in revenue for Boston Scientific in 2017 before the recall.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch.com representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch.com's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.