Duodenoscopes

Health care providers use duodenoscopes in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). These procedures diagnose and treat diseases in the pancreas and bile ducts. But design flaws made them difficult to clean. This led to several outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant “superbug” infections and scope redesigns.

Duodenoscopes are hollow, flexible, lighted tubes that allow doctors to see the top of a patient’s small intestine, or duodenum. Doctors use them in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures. The instruments help doctors diagnose and treat severe, often life-threatening, diseases such as cancer or gallstones in the pancreas and bile ducts. The advantage of these procedures is that they are less invasive than traditional surgery.

Each year, Americans undergo more than 500,000 ERCP procedures using duodenoscopes, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s website. Though, the biggest manufacturer of duodenoscopes — Japan-based Olympus — told the Los Angeles Times that the number was closer to 700,000.

Some conditions diagnosed or treated by duodenoscopes include:

- Acute pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Gallstones (small masses that form in the gallbladder and can get stuck in the bile duct)

- Infection

- Pancreatic pseudocysts (fluid-filled sac next to or outside of the pancreas)

- Trauma or surgical complications in bile or pancreatic ducts

- Tumors or cancers of the bile ducts

- Tumors or cancers of the pancreas

These devices play an important role in diagnosing and treating diseases, and they are generally safe. However, investigations by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a U.S. Senate Committee found that the devices’ designs led to outbreaks of hard-to-treat infections at several U.S. hospitals in the 2010s.

In November 2018, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) found 190 reports of so-called “superbug” infections in the United States and Europe linked to scopes manufactured by Olympus. The ICIJ and Kyodo News Service found at least 50 lawsuits pending against the company over the infections.

How Duodenoscopes Work

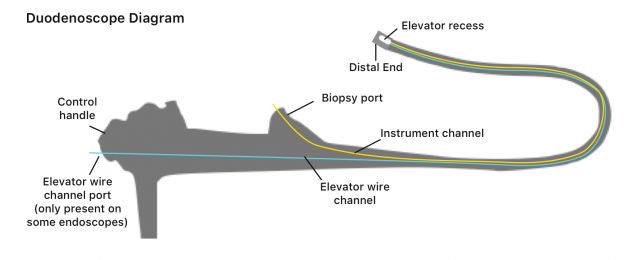

Doctors insert flexible, snake-like duodenoscopes into the mouth and pass them through the throat, stomach and into the top of the small intestine — also called the duodenum. These scopes are different from typical endoscopes used in procedures such as colonoscopies and are specifically for ERCP procedures.

“ERCP procedures [using duodenoscopes] involve the upper gastrointestinal (GI) system and allow direct access to the bile or pancreatic ducts to deliver treatment to reopen ducts that have been closed by tumors, gallstones, inflammation, infection, or other conditions,” according to the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

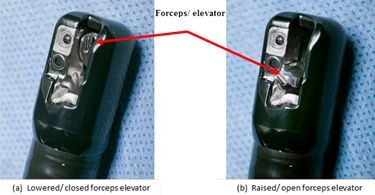

Because duodenoscopes allow direct access to bile or pancreatic ducts, they are more complex than other endoscopes. In addition to a small, lighted camera in the tip, duodenoscopes have a lever with a hinge called an elevator mechanism, explain researchers Divyanshoo R. Kohli and John Baillie in Clinical Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. This added feature makes it possible for a doctor to raise or lower accessories from the scope’s tip to perform biopsies and other delicate procedures in bile and pancreatic ducts.

“ERCP procedures [using duodenoscopes] involve the upper gastrointestinal (GI) system and allow direct access to the bile or pancreatic ducts.”

Three manufacturers — Olympus America, Inc., Hoya Corp. (Pentax Life Care Division) and Fujifilm Medical Systems, U.S.A., Inc. — market duodenoscopes sold in the United States. Olympus controls about 85% of the market, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Superbug’ Infections and Design Flaws

In the fall of 2013, the CDC alerted the FDA to a potential link between endoscopes and multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR) — bacteria resistant to several antibiotics.

The CDC investigated one of the first U.S. outbreaks in Los Angeles County at the University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center. A family of bacteria found in the gastrointestinal tract, called Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), was responsible for the outbreak.

Doctors consider CRE infections “superbugs” because they are resistant to antibiotics and are associated with higher mortality rates. The fatality rate for patients with CRE infection is roughly 50%, according to the West Virginia Department of Health & Human Resources.

In January 2016, The United States Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee (HELP) obtained data from the FDA on superbug infections from Jan. 1, 2010 to Oct. 31, 2015. The data revealed there were as many as 404 patient infections, and out of the 41 hospitals involved, 30 were in the United States. The committee’s concern was that the true number of cases may be higher than reported.

The report, entitled Preventable Tragedies: Superbugs and How Ineffective Monitoring of Medical Device Safety Fails Patients, listed several failures that allowed the outbreak to spread.

Failures included:

- Lack of reporting and timeliness or accuracy in reporting adverse events

- Lack of public or medical community awareness of an investigation into the spread of infection via the devices

- Problems with the FDA’s “outmoded” (outdated) adverse event device database

How Scope Design Leads to Infection

The risk of superbug infections is higher with duodenoscopes than other types of endoscopes because of their design. The scopes contain many small parts that make them more difficult to clean, a procedure called reprocessing, according to the FDA. Gut bacteria can collect in these small, movable parts. Because doctors reuse the scopes, bacteria left on the scope after cleaning may transfer from patient to patient. These bacteria can develop into serious superbug infections like CRE.

One of the parts where bacteria are most likely to collect is the elevator mechanism, according to The American Gastroenterological Association. In 2015, the AGA convened a meeting with regulators, manufacturers and doctors called “Getting to Zero” to discuss the problem of infection.

According to a press release from the AGA, “The problem of this infection transmission lies in the complex design of the elevator channel in duodenoscopes, which can allow bacteria to remain after cleansing, even if reprocessing follows currently accepted procedures developed and approved by the manufacturers and FDA.”

Dutch researcher Arjan W. Rauwers and his colleagues at the Erasmus MC University Medical Center in the Netherlands published a 2018 study in the BMJ’s Gut journal. They found a link between duodenoscopes and infections.

“Duodenoscopes are more difficult to reprocess compared with other flexible endoscopes. This is due to their complex design, which includes a side viewing tip, forceps elevator and elevator channel,” study authors wrote.

Furthermore, they concluded that despite cleaning, bacteria still existed on some scopes and could be a safety risk.

“Fifteen percent of the duodenoscopes harboured MGO [microorganisms], indicating residual organic material of previous patients, that is, failing of disinfection. These results suggest that the present reprocessing and process control procedures are not adequate and safe,” Rauwers and colleagues added.

FDA Regulatory Actions

The FDA investigated the outbreaks in 2013 but did not take significant action until 2015 when it ordered scope makers to conduct further studies. These postmarket surveillance studies were supposed to gather data on how health care workers cleaned duodenoscopes in “real-world settings” and how this affected infection transmission.

In December 2018, the FDA provided a safety communication with an update on these postmarket studies. It had found “higher-than-expected contamination rates” for the devices even after cleaning. The results showed that 3 percent of the scopes tested positive for “low concern organisms.” Another 3% tested positive for “high concern organisms.”

An FDA statement said the results showed that manufacturer instructions were “not sufficient” to prevent all infections. But it stressed the chance of a patient developing an infection from an ERCP procedure remained low.

The Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee criticized the FDA’s lack of action. The Preventable Tragedies: Superbugs and How Ineffective Monitoring of Medical Device Safety Fails Patients report stated that the agency “wasted valuable time” seeking cleaning data from manufacturers. The committee also said that the agency spent far too much time trying to rule out mistakes by hospital staff in carrying out cleaning procedures for the contamination.

Device Redesign and Monitoring

Despite their design flaws, no alternative to duodenoscopes existed at the time the FDA issued its safety warnings about the devices. The agency cited the importance of the devices in medical procedures in allowing the devices to remain in service despite the previous infection outbreaks. Duodenoscopes are still in use, though some manufacturers have recalled and redesigned them.

“The risk to patients of CRE infection following ERCP is low and, for most patients, the benefits of this potentially lifesaving procedure outweigh the risks,” the CDC echoed in a 2015 public statement.

Despite the danger of further outbreaks, the scopes remained in service with the defective design for another two years.

“The risk to patients of CRE infection following ERCP is low and, for most patients, the benefits of this potentially lifesaving procedure outweigh the risks.”

In September 2017, the FDA cleared the first duodenoscope with a disposable cap. The Pentax Model ED34-i10T features a single-use cap that the company claims will prevent bacteria and other contaminants from spreading from patient to patient. The first of the new devices became available in December 2017, but with 500,000 procedures performed every year, some of the older designs will remain in service for years.

“We believe the new disposable distal cap represents a major step towards lowering the risk of future infections associated with these devices,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the FDA’s Office of Device Evaluation said in an FDA news release announcing the device’s approval. A 2022 report in the journal Scientific Endoscopy noted the potential of single-use duodenoscopes to prevent the spread of infection.

New Protocols to Monitor for Contamination

In February 2018, the FDA, CDC and the American Society for Microbiology announced new voluntary protocols for standardized surveillance of duodenoscopes. The guidelines also provided standards for collecting cultures to test for contamination. The regulatory agencies drafted the guidelines — Duodenoscope Surveillance Sampling & Culturing, Reducing the Risks of Infection — in association with scope manufacturers and other health experts.

The guidelines called for collecting samples from the tips of scopes and testing them to monitor the quality of reprocessing. It also pointed out that other countries already did this type of testing.

The 57-page document provided detailed steps beyond manufacturers’ cleaning and sterilization instructions to reduce the risk of spreading infections. But the guidelines noted that “not all health care facilities may be able to implement this type of testing.”

Scope Recalls

In 2016, the FDA announced that Olympus, which manufactured about 85 percent of the scopes used in the United States, had voluntarily recalled its model TJF-Q180V scope. The company replaced the elevator channel sealing mechanism on about 4,400 scopes after receiving clearance from the FDA.

The company also updated its reprocessing manual to include a new warning. It required all users to follow all pre-cleaning and manual cleaning steps.

In January 2017, FUJIFILM removed several older models of its scopes from the market. It replaced them with a new model it believed was safer.

Pentax recalled its ED-3490TK scopes in February 2018 to modify three parts on each unit. The company also planned updates for routine maintenance in its operation manual.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch.com representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch.com's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.